- Home

- Ryan O'Neal

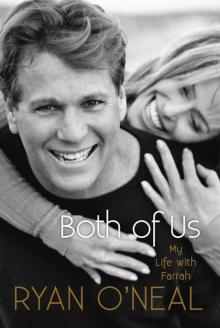

Both of Us Page 13

Both of Us Read online

Page 13

When I read these journal entries, I cringe. We had so much together, and we let it sour over everything and nothing. Who cares about a video camera? If she was having a bad day and had it in her head that I left the camera at the beach house, why did I have to contradict her? Why not just say okay, I’ll look for it, and if we can’t find it, I’ll buy a new one? I know what you’ve concluded and you’re right. If it wasn’t the video camera, it would have been something else. The two of us together had become a steaming volcano. There was so much hostility bubbling beneath the surface of our relationship that these small eruptions were our only means of releasing the pressure. Our only safe place was sex. But soon even that, the one aspect of our love for each other that was never used to hurt or humiliate, would be poisoned. And in order to breathe, we’d both seek a fresh source of air. Ironically, I’d find mine on the set of Burn Hollywood Burn, but it would be several months before I’d inhale. Her name was Leslie, an actress twenty-five years my junior who was costarring in the film. A graduate of Barnard, she was a smart girl, attractive and sweet, a decent, God-fearing Episcopalian from a small town in Minnesota who didn’t have the complexities and complications that Farrah did. Her life was much simpler. I didn’t pursue Leslie nor she me. It unfolded gradually. At first I thought of her as refreshing youth, innocent without being naive, kind without being fawning. Then one morning I realized that the first two things I’d look for on the set were my cup of coffee and her smiling face.

When I wasn’t filming, I was helping Farrah with a video project for Playboy. The editors were so impressed by the sales numbers from her cover spread that they asked if she’d do a second one. When she agreed, they suggested an accompanying video to commemorate her fiftieth birthday. She came up with the concept and it was brilliant. By this time she was serious about developing her talents as a sculptor and painter. While audiences may remember Farrah as an actress, she was also an artist. She had always wanted to try body art, in which she would cover herself with paint and use her torso as the brush painting the canvas. Playboy loved the concept so I began working with her on the production of the video. It was an arduous but exhilarating process. Despite the personal tension, she still relied upon my judgment when it came to her career. As disenchanted as we had become with each other, I couldn’t bear not to play that role in her life, and after Good Sports, I didn’t have confidence that she’d want or need me, so I was grateful to be asked.

Over Christmas, Farrah finds another cyst on her breast. Over the years, she’d had several removed, all of which were benign, but this one is in a more troublesome spot and causing acute pain. Though it turns out to be benign like the others, I was uneasy during her surgery, never imagining that it was fate’s version of a dress rehearsal. As we toasted the new year in 1997, I believed Farrah was fine and so resented the medical intrusion on our holidays because during the two weeks she was home recuperating, she was ornerier than ever. What with menopause, which had now been going on far longer than dear old mother had promised me, Farrah’s swiftly approaching dreaded birthday, and Griffin and Redmond’s growing attachment to each other, I should have smelled the sulfur. Krakatoa à la Fawcett-O’Neal was getting ready to erupt.

JOURNAL ENTRY, JANUARY 5, 1997

I fled from her last night, turned off my light, and lost myself in sleep. Farrah read my diary, a capital crime to some but not to me. She found something that infuriated her. God knows what. She tried to kick me in the groin, the most hated part of me. This with a breast full of stitches in her. I stagger off to bed and leave her throwing Christmas ornaments at my door. The disdain we feel for each other has come to the point of violence. Why doesn’t she love me anymore?

I want to stop here for a moment and say something. Yes, it’s true. Farrah and I did occasionally get physical with each other when we fought. Neither of us possessed the emotional discipline to say wait a minute, this isn’t normal, we need help. But it wasn’t the way the journalists depicted it. You have to remember that I’m a trained boxer. I sparred with the world champion Joe Frazier, and if someone is coming at me with fists flailing or feet pointed at my family jewels, my instinct is to block the blows, which is what I did with Farrah. Back then there was no YouTube, but if there had been and someone had shot footage of our skirmishes, it would have generated millions of hits not because of the violence but for the slapstick dance. I’m not trying to make light of Farrah’s and my tussles with each other; still, most of the time, I found her outbursts oddly endearing because they were so ludicrous, so childlike. They were also courting serious injury. I should have paid more attention to the signs that something was amiss, that something was building, growing, and might one day explode. It had been percolating for years. But I was bedazzled. I loved everything about her, even her infantile display of temper, which I associated with her being fiery and passionate. By 1997, her conduct unbecoming was more likely to ignite anger than bemusement, and in defending myself I didn’t see my behavior as aberrant. Most men of my generation would have reacted the same way. That doesn’t make it right.

But there was so much not right during this period that how we fought was simply one more obstacle to finding our way back to each other. Another, which I’m only beginning to recognize now, is that Farrah and I took most everything too personally. We may have seemed as confident as Ken and Barbie, but underneath, we were unsure of ourselves. If she was in a bad mood because of a tense moment on set or a dispiriting article, and she snapped at me, I didn’t have the wit to stand back and say, “She’s not really angry with me, it’s that cretin of a reporter from the National Enquirer.” Farrah was the same way. She interpreted a lot of my bad behavior personally too, when in reality, most of the time, it wasn’t her I was lashing out at, it was my kids, the world, Hollywood, my agent, you name it. I’m a moody guy, as are many actors. I’ve walked out of the middle of my own dinner parties. It doesn’t even require a trigger.

Our anger was misplaced. Farrah and I should have directed it toward the shared enemy lurking outside our front door, the same one I saw reflected in all those tired smiles on my dad’s low-budget movie sets: aging in an industry that genuflects before the altar of youth. The downward spiral in many show business careers has more to do with the year you were born than with your talent. Even when your expiration date arrives, you keep on going, hoping no one will look too closely at that number stamped on your forehead. Farrah and I both feared it. We never discussed it, probably for the same reason we didn’t talk about James Orr. We wanted to keep pretending it wasn’t real. But the truth of our business is that the older you become, the more meager your opportunities for work. When you’re starting out and going on auditions, you have a future to look forward to; when you get to be our age, it’s the reverse, and there’s a terrible reluctance to admit the transition. Look at what I’m doing now in my dotage: cable television. At least Tatum didn’t force me to try out for the reality show. And Arthur Hiller would never have directed Burn Hollywood Burn, a comedy with a substandard budget and (sorry Joe) a controlling screenwriter/producer, if he were still in his prime. And speaking of dramatic irony. The movie is about a director who ends up hating his film so much that he steals the reels to prevent it from being released. In real life, Hiller so disliked the final cut of Burn Hollywood Burn that he insisted on having his good name removed from the credits. I was an actor. I didn’t have that option. What was I supposed to do, have special effects black out my face?

I had passed the half-century mark by 1997, and while it haunted me in quiet moments, I had survived that initial wave of psychological nausea. Farrah hadn’t. Weeks away from her fiftieth birthday, she was in a panic, the all-American girl now tormented by the same beauty that catapulted her to fame and that she could see was fading. Farrah was notorious for being tardy, but at this point in her life, it had gotten perverse. She would spend hours in the bathroom, staring at her face in the mirror. Once, early in our relationship, we were late for a dinner wi

th the president of the United States and Nancy Reagan because I couldn’t convince Farrah that she really did look fine. Over the succeeding years it got worse. I watched her slowly being consumed by insecurity, but I couldn’t fully appreciate her anxiety. I would tell her, “You’re beautiful, what are you worried about?” And to me she was beautiful, still exquisite. But instead of being patient with her fears and reassuring her, I felt offended that my word wasn’t good enough.

As the clock ticked, so did the time bomb. One moment Farrah and I are making love, and I’m reading to her, and then she’s whipping up a batch of chili con carne just the way I like it; the next, she’s dictating a press release to her publicist announcing our breakup. Some days we’d argue by voice mail, and there would be a dozen incoherent messages on both machines. There were nights as I lay in bed listening to the surf while drifting off to sleep I ached to have her in my arms and would keep telling myself I could learn to adjust to the fractious tone that had come to define our time together. On some of those nights, I would pick up the phone, start to dial, and then stop myself. Was it fear or survival? I’m not sure. What I do know is that I couldn’t bear the thought of leaving her any more than I could imagine our staying together. If I was in hell, Farrah was in purgatory. I had to breathe or I would have suffocated. So I finally inhaled the cool fresh air of Leslie. I wouldn’t have succumbed if I could have seen into the future. I weakened. I didn’t turn to anyone for advice. The one person I would have talked to about this was Blackie, and he was gone. He would have told me to stick it out with Farrah, to fight harder to save what we had. By Farrah’s fiftieth birthday, I was torn between the girl who was helping me to catch my breath, and the only woman who was ever able to steal my heart. The day of her birthday, she didn’t want a party. She had lunch with a few of her girlfriends, and that was it. Then she came to the beach house. We made love like the old days. It was magical, out of the pages of a fairytale. Come morning, the spell was broken, and soon both the princess and the prince were again wandering aimlessly, trying to find their way from once upon a time to they lived happily ever after.

Two weeks later, Farrah and I are where we were before, at each other’s throats, then in each other’s arms, then at each other’s throats again. The difference now is that I can’t rationalize it anymore and neither can she. At her request, I’m boxing her things at the beach house and arranging to have them moved to her place on Antelo. But disentangling ourselves from the cord of unresolved emotion won’t prove as easy as packing boxes. Each night when I get home, I drop my keys on the table, pour a glass of wine, walk over to the phone, and stare at the blinking red light on my answering machine, tensing as I push the button to hear my messages. I suspect Farrah was engaged in the same sad exercise at her house. Voice messaging had now become our intermediary. A cold, metal contraption, that’s where we vented our disappointment with each other. It became our catch-all, be-all, end-all, chicken-shit way of dealing with our troubles. I remember one night when she called late. I saw her number on my caller ID. I hesitated for a moment before answering, expecting another tirade. Her voice was soft, almost timid. She asked if I’d stay on the line with her while she said her prayers. Later I wept.

By now all the drama in our life was heartbreaking. I was at the beach house and had been inhaling and appreciating Leslie’s aroma much the way one might a fine glass of wine. I knew there was something delicious there. I was ready to take a sip. Farrah calls and says she wants to come down to the beach.

“It’s eleven o’clock,” I say. “It’s too late. Let’s meet tomorrow.”

“I want to come now.”

“No, Farrah.”

Leslie’s listening. “Are you one hundred percent sure she’s not going to come over?” she asks.

“Absolutely,” I answer. “Farrah has her pride.”

Truthfully, I was only 80 percent sure, but I figured the odds were with me, and I had locked the door just to be sure. At two in the morning I hear someone coming up the stairs and I gulp. In my groggy state, I briefly consider scaling down the terrace out to the beach and making a run for it, but then I remember my bad knee. I lean over and frantically begin whispering to Leslie, “Get up! get up!”

Farrah walks in.

Leslie and I are naked in bed.

Farrah must have let herself into the garage and gotten the house key out of my car.

Leslie pulls the covers over her head. I jump out of bed and pull on my shorts, putting both legs in one hole. Farrah is furiously yanking at the covers to get to Leslie, and I’m bouncing around mostly nude, sputtering inanities such as “This isn’t what you think.” By now Farrah has practically stripped the bed and is giving Leslie this withering, Bette Davis stare.

“What’s your name,” Farrah demands.

When Leslie doesn’t answer, Farrah utters a warning, turns on her heel, and leaves, collecting photos and other things on her way out, personal items, including one of our beloved cherubs. I stumble down the stairs after her, trying to explain. I feel terrible and embarrassed for her, and I want to comfort her. I tell Farrah that Leslie isn’t some girl I just picked up, that this is a woman I genuinely care about. I know, I know, not the smartest thing to say under the circumstances, but this had never happened to me before. In the eighteen years we’d been together, I’d never cheated on Farrah, not once. Now the boundaries of our relationship were blurred. We were living separate lives, and I wanted Farrah to know that I wouldn’t just hop into bed with anyone. It would have to be with someone important, that I would never dishonor all that we had once shared by having casual sex with strangers. Farrah looks crestfallen, depleted of energy or caring. I thought I was saying all the right things but then realize what she must have been hearing, that I’d replaced her with a younger woman. That wasn’t the case. Farrah had simply become too exhausting. I needed a breather. Leslie took care of me the way I once took care of Farrah, and it was great to be on the receiving end of gentle affection again. She was my nurse, my friend, and my confidante. I wanted her respect, and I measured the choices I made by what she would think of me. But the longer Leslie and I were together, the less hope she had in a future for us. Rather than our relationship strengthening over time, our connection would weaken because Farrah still inhabited her own room in my head.

Leslie and I would be together for four years. That relationship would be the most peaceful of my adult life. It would show me that I was capable of a mature, reciprocal relationship in which two people treat each other with respect and understanding. Leslie and I were, dare I say it, a normal, healthy couple. We never had fights because she insisted on talking things out. Though I admit I wasn’t always the best student, she taught me by example the benefits of mutually engaging conversation. Most people assumed that I was beguiled by her youth. It was a lovely bonus, but not the prize. She possessed a wisdom, a sanguinity, and after a while both began to rub off on me and I started to like myself again. I began to remember how good it felt to be kind and generous and have it appreciated. Farrah saw all this too and was tortured. From the moment she discovered Leslie and me together that night at the beach, she slowly became rueful. I wouldn’t understand just how much until recently when I made a disturbing discovery in one of my journals. That’s all to come. Let me continue with the autumn of our discontent.

It didn’t take long for the press to swoop down on the three of us. They were unrelenting. They staked out Farrah like a bail bondsman waiting for a fugitive. Photographers surrounded the house in Malibu. They tried to catch me going in and out of my gym, and they hounded Leslie. The poor girl was portrayed as the “red-headed floozy who stole Farrah’s man,” a Los Angeles Lolita. This was a small-town girl who wasn’t used to being sullied. It was hard on her. That whole year is a blur to me now. Perhaps it’s my mind’s way of protecting itself. Here are the highlights, not necessarily in proper order.

Patrick and actress Rebecca DeMornay, who had been dating for a while, have their

first child. They’ll have another daughter in 2001. I establish trust funds for both, as I had previously for Griffin’s children. Rebecca doesn’t say a word to me.

Farrah’s cast opposite Robert Duvall in The Apostle. She owns the part. I help her rehearse. Tracy and Hepburn couldn’t have worked together as successfully in the wake of what she and I had just been through. That made it even harder. We could walk away, but we couldn’t let go …

JOURNAL ENTRY, FEBRUARY 24, 1997

I saw Farrah at the gym today. It was our first meeting since it happened. She was wonderful and beautiful both. We cried together and I held her head. She asked if she could keep the ProGym shirt I was wearing, so sweet, she said, was the smell.

Nothing about Farrah and me seemed to have clarity. We couldn’t even break up properly. I remember when Redmond fell on his skateboard and got a nasty scrape on his arm. He was still wearing the Band-Aid a week later, and it had become soiled and ragged, half of it dangling. He’d peel at it slowly, painfully, wincing from the sting of the adhesive tearing at the fine hairs on his skin. So one morning, I reached over and yanked it off. “See, that didn’t even hurt,” I said. He gave me a dirty look, and then admitted that my method was better than trying to remove it a millimeter at a time. That’s what my relationship with Farrah felt like at this point, like a Band-Aid hanging from a wound, with each of us waiting for the other to pull it off. Instead, like Redmond, we both picked at it reluctantly, with not-so-gentle results. And then there was the infamous appearance on the Late Show with David Letterman. I didn’t think it was so bad. I knew what she was trying to do. Her spread in Playboy magazine, the one for which we’d done the video, was coming out and she was attempting to play the part of a ditsy bunny, thinking it would be a clever way to promote the magazine. She called me that night in tears, saying that after the taping she was in the bathroom and overheard a group of women making vicious comments. “They thought I was on drugs,” she said. I told her, “You’re a fox, you’re not a bunny, just let the photos speak for themselves and don’t feel you have to be anyone other than yourself in these interviews.” That stopped her tears but not the assault. Several months later the infamy was repeated, this time by the Star.

Both of Us

Both of Us