- Home

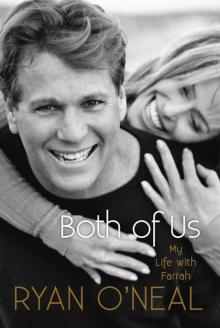

- Ryan O'Neal

Both of Us Page 3

Both of Us Read online

Page 3

I give my daughter not one but two cars—a brand-new BMW and a classic MG sports car. I had them brought to the front of the house. Each had an enormous ribbon with a bow tied around it. The entire party escorts Tatum outside. I expect an ordinary teen response from her, a squeal, a little jumping up and down, a big hug for her old man. Instead there’s nothing. She just looks at the cars and then at me. I can’t tell whether she’s confused or disappointed. “Thanks, Dad,” she says as she turns and walks back into the house. By this point it’s clear I’m not going to able to console my daughter with fancy presents. The stronger Farrah believed in me, the less Tatum did. When I met Farrah, I felt that she was a godsend and that my only daughter would agree. It wasn’t fair assuming my daughter could think like an adult. I had treated Tatum as if she were a grown-up since she was nine, not a healthy approach to a child. Farrah can only enhance us, I thought then, which under normal circumstances should have been the case.

I now realize “normal” had long since been an impossibility for Tatum and me. I truly believe that if Tatum and I had not made Paper Moon, she would be dead, because she would have been with her mother and she wouldn’t have had the escape route that I gave her. She would have been a teenager in that erratic life with the worst of all adult behavior to imitate. First, I saved her, made her my whole world, and then I pushed her out.

I remember once, out of frustration, actually trying to explain to Tatum: “You’re asking me to choose the girl I don’t sleep with. You can’t ask that of a man. You’re missing one of the chief ingredients of a relationship. I love you, you’re my daughter, but there are certain aspects of my life you cannot fulfill.” The words came tumbling out of my mouth before I realized what I’d said. I’d inadvertently complicated our relationship. It was utterly inexcusable. I was blinded by love and in my naïveté I expected my child to sympathize with me. I kept telling myself that everything was going to be okay, that we could step blindly into that blue yonder of the faultless American family. Except there was already too much spoiled fruit on the family tree.

My mother saw what was happening and understood I would have to leave Farrah to get Tatum back. My mother didn’t want to say that. She also knew I wouldn’t do it. Both my parents did. My dad, Blackie O’Neal, was a well-known screenwriter and my mom, Patricia, a respected if occasional actress. They were familiar with the impermanence of Hollywood relationships. They knew my first two wives, and saw Farrah as an oasis of calm and responsibility. They also realized that the more I fell in love with her, the more Tatum would retreat. It might have been different had I enforced healthier boundaries beginning with the filming of Paper Moon, where father and daughter were equal partners, but we acted like adult friends, and it would prove our undoing.

But at the start, Farrah and I are still confident things will work out with Tatum, so we’re concentrating on building our life together. Also that November, trouble is brewing on another front. Lee calls from Canada with an apparent change of heart and tells me to stay away from his wife, or else. I tell him I can’t do that because I love her. He repeats, “Stay away from my wife and stay out of my house!” We hang up and my adrenaline is pumping. I share this news with Farrah, who says that Lee wrote her a note about how I am only after publicity, trying to exploit her fame. He has no clue how much she means to me. He calls me back the next day, I suspect prompted by Farrah, to apologize for threatening me. I can see why Farrah was once in love with him.

Farrah and I go to New York together before Christmas. She has some personal appearances scheduled for Fabergé shampoo; she’s their spokesperson, and I decide to tag along. We would make one of our lasting memories on this trip. I’ve booked us into the Pierre Hotel, on Fifth Avenue overlooking Central Park, my favorite hotel at the time. After we unpack, I tell Farrah, “On the top floor of this building there’s a deserted ballroom, and all the plaster of Paris cherubs that must have been on the ceiling are now just lying on the floor.” The Pierre was about to undergo an extensive renovation. I see her eyes light up with angelic anticipation.

“Let’s have a look,” I say. “We have to take the elevator as far up as it will go, and then climb a staircase. I don’t think we’re allowed up there, so we’ll have to sneak around.”

“Let’s go,” she whispers. We do and we find the cherubs. They must weigh twenty pounds each. And there she is, bending over, picking up these ornaments, and trying to balance them in her arms. I have the flashlight.

“What are you doing?” I ask.

“That one, and that one,” she says, pointing. “Oh, there’s another good one behind you!”

These are not tiny keepsakes, mind you, they’re big and heavy, each one like a miniature chubby Buddha. We take as many as we can carry downstairs and then have the bellhop deliver boxes that we pack with our loot. We take four home with us and they remained in our family room for years. I still have one at my beach house. Farrah and I would often reminisce about this trip—her struggling down that flight of stairs making loud banging noises as she wrestled the fat, unwieldy statues. That was my image of her forever: hunched over, sweating and laughing, moving those things in the dark. For years I would imitate her, bending over, pretending to be carrying something enormous, trying to get down the stairs with too many cherubs.

Though I smile looking back on Farrah’s formidable display of physical strength that day, she wouldn’t always have such vibrant health. Worrisome things would crop up from time to time that would be successfully treated and go away. But back then, neither of us gave them a second thought. We were young and full of life, eager to begin our future together.

The first of these scares comes right before our first Christmas together, in 1979. Farrah develops a group of benign cysts on her breasts, six of them, that must be surgically removed. (Over the years, she’ll end up having many more.) She goes home to Texas for the procedure. While I stay in LA at her request, Lee reasserts himself, racing to Houston to support his wife, and then returning with her to LA to nurse her back to health. It’s clear that Lee is making a final attempt to win her back and she’s too weak and too tired to resist his caretaking. Though I’m deeply annoyed, Farrah keeps reassuring me that our love is safe.

JOURNAL ENTRY, JANUARY 5, 1980

Lee has gone to Houston and has returned home with her. I’m hurt and confused. Farrah called and said not to worry because she loves only me. Not very consoling when I know they’ll go back to the same house and with the captive eye of her mother, who’s come with her.

JOURNAL ENTRY, JANUARY 6, 1980

My girl is back but can’t talk to me because Lee is in the house and watching her closely. Why is he still there? I spoke to her briefly and she sounded conflicted. I have lots of questions for this girl. Definitely not yet my idea of an independent woman, although I recognize her sense of propriety. She still feels an obligation to Lee, but is not sure how to honor it. I’ll be patient with her. It seems I have no real choice short of firing her before she fires me.

She finally called. It was sweet, but slightly hurried as Mr. Majors was in the shower. I was abrupt and she quickly called back pleading for understanding and professing never before finding love as she has with me. I believe her and it made me feel relieved.

It turns out Farrah’s mother will not soon be my ally. Lee doesn’t stay at the house long. He’s doing a movie and has to go back on location, so now Lee’s gone, and I’m here in Los Angeles. I meet Pauline for the first time. She’s staying with Farrah until she’s fully recuperated. She has a very deep southern accent. She’s a quarter Choctaw Indian, high cheekbones, an older woman but striking. She’s strong and stoic, not at all impressed by Hollywood fame and glamour. She’s been the one sturdy constant in Farrah’s life and Farrah depends on her for advice and emotional support. Farrah also has an older sister, Diane, who lives in Texas. She and Farrah, though loving sisters, share few interests and so they seldom chat. Diane sometimes helps Farrah with PR, without ever br

eathing the air of Southern California. Her doing Hollywood PR from the Lone Star State always amused me.

I’m up at the house with Farrah. Lee’s moved out and they’ve filed for divorce. We’re watching television in her bedroom, and the doorbell rings and it’s Jay Bernstein, with his fiancée. Jay’s a too slick character. He was Farrah’s manager for a while until she finally gave him the boot because he treated her like a dull-witted child who also happened to be a meal ticket. He managed Suzanne Somers too. Farrah told me how Jay used to think nothing of doing her newspaper and magazine interviews, telling the stunned reporters, “You don’t need to talk to Farrah because I know exactly what she would say.” Jay had always been close to Farrah’s mother. He was smart. Flowers on her birthday, that sort of thing. And he was always working the mother because he knew Farrah listened to her. So Pauline had some affection for him. Farrah lets him in the house with the fiancée, and I can hear them going into the kitchen, already arguing about late, unreliable financial reports. Farrah sounds furious. I’m still in the bedroom. There’s this long hallway with photographs lining the walls, and I hear Pauline saying to the fiancée, “And this is Farrah when she was three years old, and this is her when …” Suddenly there’s a terrible crash in the kitchen. I bolt down the hall, go flying past Pauline, who keeps on pointing out pictures to this woman, “… and this is Farrah making her first communion,” she continues, never even looking up, as if this sort of thing happened all the time. As I run into the kitchen, Farrah is throwing a frying pan at Jay. Now these are the kinds of frying pans you have to grip with two hands. I yell, “Stop, you’ll tear your stitches.” It’s a lethal throw that fortunately misses. I say to the man, “I don’t know how you riled her but you better go before she picks up another pot.”

It’s my first glimpse of Farrah’s temper. I’ve been careful so far to keep that part of me disguised. I try to tell myself that truly passionate people are like that; it’s what makes us who we are.

I want to win Pauline over, so I take Farrah and her to Chasen’s, and invite my mother to join us. Farrah always loved Chasen’s chili. Fred Astaire is in the entranceway when we arrive; he escorts us to our table and does a few dance steps, a dazzling start to our evening. There are lots of show business people and everyone is extremely friendly. Chasen’s is the gathering spot for Hollywood’s elite. Hitchcock is there that night. Though dinner goes well, and both mothers are polite to each other, it’s hard not to see that they have nothing in common. My mother is cultured and Pauline has a third-grade education. Don’t get me wrong: Pauline isn’t dumb by any stretch, but she’s limited. She also has no interest in show business whatsoever, thinks Farrah should come home to Texas. I can tell Pauline doesn’t like me. I think it’s because she doesn’t approve of Farrah’s being involved with another man before she’s divorced. She never does warm up to me, though Farrah’s dad, Jim, and I will become the best of buddies in the coming years. We share an interest in history. On the way home from Chasen’s, there’s a program on the radio about Lord Mountbatten. The women are dozing, so I listen. The IRA assassinated him in Ireland, blew up his sailboat with him and his young grandson in it. I’m all for the reunification of Ireland, but can they only get there by killing?

After Pauline goes back to Texas, Farrah is still in pain. At the time, I owned a house in Big Sur. Lee is still on location with the movie. I decide to take Farrah there to heal. We take the Pacific Coast Highway, the PCH, driving along some of the most magnificent vistas anywhere in the world. Hours later, we’re winding through the mountains, it’s late at night, an enormous storm hits, and we get caught in a rock slide. As I’m trying to weave through, we’re trapped by a huge boulder in the middle of the road. Suddenly, fearless Farrah, with her chest still full of stitches, opens the door, steps out of the car into the torrential rain, and says, “Help me move that thing!” I reluctantly get out and together we start pushing. I can feel the mud rising up past my ankles. Then there’s another stranded motorist flapping his arms at us, screaming, “Landslide, landslide, get out of there, are you crazy?!”

“Honey, they’re saying we’re crazy,” I shout against the pounding rain, hoping she’ll retreat to the car.

“Just keep pushing,” she says. “We can do this.”

After a few tries, we’re able to move the damn boulder enough to squeeze the car past it.

The rest of the ride, thankfully, is uneventful.

Big Sur is both soothing and exhilarating. Henry Miller used to live nearby. He would send everyone notes at Christmas, telling the recipients the presents he wanted. He once asked me to buy one of his own books for him. Later he would be ensconced near me in Pacific Palisades with his Japanese wife, who, I’m told, never stopped nagging. Henry told people she may have thought she had married a rich man. He was only famous.

JOURNAL ENTRY, JANUARY 10, 1980

We relax slowly and soon she’s cooing and then the comedy of me fumbling around trying to enclose us from the Big Sur night. She giggles till she falls asleep and I lie next to her with great expectations in my heart, for she is beginning to endear herself to me. Next morning, I shower with my girl, a fine way to kiss and cuddle.

JOURNAL ENTRY, JANUARY 14, 1980

So far it’s a little bit of heaven. We’ve had a relaxed evening by the fire with Van Morrison playing in the background. We talk at length about assorted problems like husbands and wives. Lee is packing at their home as I write this, probably for the last time.

We talked long into the night and finally slept. That we are still together amazes me. I guess it’s because I’m just not used to having such a pure beauty like her and it still makes me wary. I feel a lot of powerful urges and I want to make sure that I act only on the good ones. I’m sorry we’re leaving so soon tomorrow, but it’s been very fulfilling in a lot of ways. Especially to me. We talk because there’s no TV, no movies, a chance to get to know each other. I do want to go all the way with this.

JOURNAL ENTRY, JANUARY 17, 1980

Our last day in this magnificent seascape surrounded by ancient cliffs and trees, we shop at a bakery with irresistible smells. The drive home to LA is exhilarating. Three weather changes and all the colors the sky affords and I’m riding with my own rainbow. Straight to the heart. I felt Farrah slip out of bed early this morning, so I went to join her. I want to tell her stories, dance around the room to Stephen Stills, and then take her to lunch at the Brown Derby. A sad spot was the call from Tatum. She’s fought with her mother again. I listen to her story and know it’s beyond me. I turn to Farrah for help.

Farrah’s visibility is on the rise. She’s shot another cover for Vogue, is completing the last of her Charlie’s Angels appearances, which she’ll be talking about with Barbara Walters, and she’s beginning to get some interesting made-for-TV movie offers. Meanwhile, my career is in a slump. The follow-up films after Paper Moon, including the entertaining comedy The Main Event, with Ms. Barbra, did nothing to bolster the industry’s respect for my acting. But the great lost opportunity was The Champ. A huge success, it made Ricky Schroder a star and revitalized Jon Voight’s career. That could have been Griffin and me. I was cast as the father, Griffin was promised the son’s role, but the studio changed its mind about him so I walked. I was proud of how my son dealt with such a severe disappointment. He took it much better than I did.

And now I’m reading the script for The Hand, and Sue Mengers is convinced I’ll get an offer. I’ve also been given the script for The Thornbirds. In the end, I won’t get either role. Michael Caine will be cast as the lead in The Hand, and The Thornbirds, instead of being a film, will be turned into a television miniseries starring Richard Chamberlain. I want to work, but the offers aren’t coming. I find myself increasingly interested in Farrah’s career, which is at a turning point. She wants to extend herself but doesn’t know what form it should take. This is where I see an opportunity. If I can’t help myself, maybe I can help Farrah by bolstering her confidence. S

he doesn’t realize what her gifts are, thinks they’re just her hair and smile.

I’ve come to believe that a lot of love is about admiration. Farrah has some acting licks. For one thing, she can read a scene and own it, just read it once and know the lines word perfect. All she needs now is the chance to play a role that has nothing to do with beauty. The opportunity arrives that spring of 1980 with a made-for-TV movie called Murder in Texas. This is a true story about a doctor with a mistress who loses interest in his wife and slowly poisons her to death—the wife, not the mistress. We pull Farrah’s hair back into a ponytail. She has these tiny ears that are adorable; they’re endearing. We downplay her makeup and wardrobe, and voilà, the actress emerges. She’s brilliant in this part, so believable. It would mark the beginning of many similar successes. I enjoy coaching her, helping her run lines and hone her craft. I’ve surprised myself.

This was the love I had not known before. I had known the kind of love that children have for their parents, but that’s expected; this was very different. Since my marriages, I’d practiced serial monogamy. I liked smart, unpredictable women, such as Anjelica Huston, but I never fell in love and I had no intention of getting married again. Farrah and I enhanced each other in ways I’d never experienced. I grew up a Catholic, but I had fallen away. I had two ex-wives when I met her. You’re not supposed to get divorced in the Catholic Church and I did it twice. I didn’t have a parish; I didn’t have a priest whom I could speak with. Farrah wasn’t lapsed. I started going to Mass again because I could accompany her. We’d get dressed in our Sunday clothes and go to Mass together every week.

Both of Us

Both of Us